By Cynthia Ann Brassington, Esquire and Francis C. Thomas, CPA, PFS

This article was first published in the New Jersey State Bar Family Lawyer Journal, April 2019.

Baby boomers are now retiring today and divorces among Americans are on the rise. Divorce for people 65 and older has doubled. According to the Pew Research Center, the divorce rate for people 65 and older has “roughly tripled since 1990, reaching six people per 1,000 married persons in 2015.”[1] With the increase of gray divorces, it is imperative that the family law practitioner have a general understanding of Social Security benefits and how they affect our clients in both their financial need and their ability to pay.

Baby boomers are now retiring today and divorces among Americans are on the rise. Divorce for people 65 and older has doubled. According to the Pew Research Center, the divorce rate for people 65 and older has “roughly tripled since 1990, reaching six people per 1,000 married persons in 2015.”[1] With the increase of gray divorces, it is imperative that the family law practitioner have a general understanding of Social Security benefits and how they affect our clients in both their financial need and their ability to pay.

Decisions regarding Social Security (SS) can be deviously complicated. There are thousands of rules, thousands upon thousands of additional codicils to clarify the rules, annual changes, and recent legislation, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA), which drastically modified the planning landscape. Each day 10,000+ “baby-boomers” reach retirement age and many other individuals of pre-retirement age make critical choices impacting their potential SS benefits. These decisions involve when to claim benefits, what kind of benefit to request, and when to marry, divorce, or remarry. It is essential that the family law practitioner consider the value of SS when evaluating alimony. This article provides an overview of the SS benefits, to assist the family law practitioner to better advise their clients in understanding the financial impact of divorce, alimony, and remarriage.

How are the benefits calculated?

For the family law practitioner, it is imperative that he or she understand the significance of full retirement age (FRA), a client’s earnings record, and benefit options. In order that the obligee will receive an accurate analysis of their “need” and the payment obligation of the obligor in their analysis of their ability to “pay.”[2] SS is a valuable resource providing 90% of the cash flow for one-third of the retirees, up to 28% of the cash flow for high income retirees.

How does Social Security work? To receive retirement income, a worker who is born after 1928, must have at least forty (40) quarters of coverage (QC) credited to his or her work history,[3] a maximum of four quarters per year. Credits are a function of dollars earned and not calendar quarters worked. The QC requires that the worker earn at least the equal required minimum, which is adjusted annually for inflation.[4] In 2018, the worker must have earned $1,320 per quarter, or $5,280 for the year.[5]

The Social Security Administration (SSA) calculates a worker’s benefits using a multipart formula that first converts annual income earned over a worker’s career into today’s dollars. The annual income used is the lower of what the worker earned for the year or the maximum Social Security base wage for that year. The maximum SS base, which adjusts annually, is $128,400 in 2018. The SSA selects and sums the 35 highest inflation-adjusted yearly earnings. The sum is divided by 420 (35 years times 12 months per year). The result is the Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME), which is used to calculate the Primary Insurance Amount (PIA). The PIA is the monthly benefit that a worker will receive at Full Retirement Age (FRA). The benefit formula is progressive (low earners receive a greater proportion of the pre-retirement income) with three tiers. The first $885 of PIA is multiplied by 90%, the next chunk up to $5,336 is at 32%, and the amount over $5,336 up to the annual maximum is multiplied by 15%. In 2018 the PIA is $2,788.

Full retirement age (FRA) which is based on the worker’s year of birth. If the individual is born before 1938, he or she reaches full retirement age at sixty-five (65). Individuals born between 1943 and 1954 reach full retirement age at sixty-six (66). The following table reflects full retirement age for persons born after 1954:

| 1955 | 66 years and 2 months |

| 1956 | 66 years and 4 months |

| 1957 | 66 years and 6 months |

| 1958 | 66 years and 8 months |

| 1959 | 66 years and 10 months |

| 1960 and forward | 67 years |

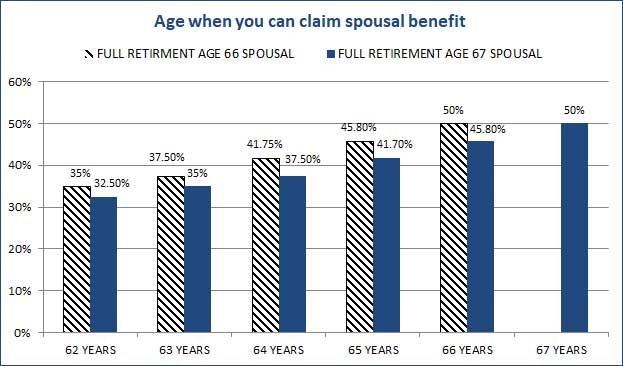

Understanding the credits is one part of understanding Social Security. The amount of the Social Security benefit that will be received by an individual varies not only on their individual work history, but also on the work history of their spouse, and when they take the benefit, either by early or delayed retirement. For example, an individual that is eligible for full retirement at age sixty-six (66) can elect to take a reduced benefit as early as age sixty-two (62.) If an individual who would reach full retirement age at age sixty-six (66) takes their benefit at age sixty-two (62), the reduction is 25%. The chart below shows the earliest age to claim benefits the maximum reduction for filing early.

It is recommended that both counsel and the clients obtain a copy of their SS statement of benefits by visiting the website at www.ssa.gov/myaccount. Taking SS benefits before FRA results in a reduced benefit, and delaying retirement beyond FRA up to age 70 increases the benefit as the worker accrues a Delayed Retirement Credit (DRC).[6] By way of example, by delaying collecting SS post FRA, the worker accrues a DRC for each month until reaching age 70. The DRC is 2/3% per month or 8% per year (not compounded). For those born from 1943 to 1954, forgoing benefits until age 70 increases worker benefits and survivor benefits by 32%. The life expectancy for a 66 year-old male is 84.5 years and a female is 86.9. There is no advantage to waiting to commence benefits beyond age 70, as the PIA does not increase beyond age 70.[7] The decision when to commence collecting Social Security is a function of a great many variables. The most important factors are sufficient retirement assets and life expectancy. The current PIA maximum SS at age 70 is $3,698 per month.

Eligibility for spousal benefits

Married and qualified divorced individuals are eligible for benefits based upon their own records as well as spousal and survivor benefits. If claimed at FRA, spousal benefits are equal to 50% of the PIA of the worker and survivor benefits can be equal to whatever the worker was collecting at the time of death. As previously stated, the PIA is basically the worker’s FRA benefit amount. A current spouse needs to be married for at least one year to qualify for spousal benefits and the worker needs to have filed for benefits. In order for an ex-spouse to qualify for spousal benefits, however, they must be unmarried, their ex needs to be eligible for retirement benefits or disability benefits, the marriage needs to have lasted for at least 10 consecutive years, and they must have been divorced for a least two or more years or the ex must have filed for retirement or disability benefits. Survivor and ex-spouse survivor benefits can start at age 60 or at age 50 if disabled. For survivor benefits the ex-spouse needs to be unmarried unless the remarriage was after age 60.[8] SS has created a strong motivation to stay married for the required ten years. If a client is close to the ten year mark, it may assist both parties by delaying the finalization of the divorce. If the former spouse claims his or her Social Security benefit before reaching full retirement age, at age sixty-two (62) for example, and the worker spouse has not yet reached full retirement age, it will reduce the spousal benefit by the actuarial reductions from the 50% share if he or she has not reached full retirement age.

Deeming and the Bipartisan Act (BBA) of 2015

Deeming is another obstacle for individuals filing for worker and spousal benefits before FRA. This rule requires a claimant to collect the higher of the benefits based upon their own record or eligible spousal benefits. This means that a spouse or ex-spouse cannot file a restricted application to collect spousal benefits while their own worker benefits grow via DRCs. Deeming originally only applied to recipients age 62 to FRA. However, the BBA of 2015 extended the deeming rule from FRA to age 70 for individuals who had not attained age 62 by January 1, 2016.

Another aspect of the new law (for those individuals not grandfathered) is that a current spouse can collect spousal benefits only if his or her spouse applies and collects worker benefits. If the working spouse is at FRA and attained age 62 by January 1, 2016 (not subject to deeming rule since reaching FRA), they have the option to collect worker’s benefits based upon their own record or spousal benefits. Choosing the latter option requires filing what is called a “restricted application” and permits their own worker benefits to grow via the DRCs. Spousal benefits do not increase by DRCs and they do not increase by the worker’s DRCs. Therefore they should be taken no later than FRA. “File and collect” has replaced “file and suspend” since the passage of the BBA 2015. Workers who filed and suspended prior to April 30, 2016 are grand-fathered. Understanding the implications of spousal benefits is extremely important in order to maximize benefits.

The Panetta offet

There are workers employed in government positions who do not pay into the Social Security System, such as federal workers employed in the Civil Service Retirement System (CSRS), hired in 1983 or before, and police officers of some municipalities, for example. When representing these clients, consider including in the Marital Settlement Agreement the anticipated offset that may arise upon full retirement for both parties, if one of the parties will receive SS benefits. For example, assume that the parties are in a long term marriage, and husband is employed by the City of Atlantic City as a police officer. He has an excellent pension and does not pay into SS, and there is no question that his defined benefit plan is completely marital. Further assume that his wife is employed in a job with no pension and she pays into SS. Both parties are 58, and the husband retires, and he commences to collect his pension, now in pay status. The wife continues to work. The parties divorce when they are both 60, and a Domestic Relations Order (DRO) is entered, that provides the wife receives 50% of the coverture fraction of the husband’s defined benefit plan pension.[9] The wife was born in 1954 and therefore, she is eligible for FRA at age 66. Here is the inequity. The husband has 50% of his pension; the wife has 50% of his pension and she has 100% of her SS benefits upon her retirement at age 66; therefore, the wife has greater retirement benefits than the husband.

In these cases, the SS benefit may be offset by the pension by a formula. This is the issue that arose in Panetta v. Panetta, 370 N.J. Super. 486 (App. Div. 2004), wherein plaintiff-husband, Anthony Panetta, was employed in the private sector for 19 years, and then went to work for the federal government in 1977. He had retired and was receiving both a federal pension and $530 a month in SS benefits. The defendant-wife, Carolyn Panetta, was not yet retired, employed in the private sector for the length of the marriage and earned SS benefits. The parties had included in their Judgment of Divorce: “It is understood by the parties that the evaluation of plaintiff’s pension reflects an adjustment for imputed SS benefits as it is a civil service pension. This reduced valuation shall be utilized for division of plaintiff’s pension and the application of a Qualified Domestic Relations Order unless New Jersey Courts dictate law to the contrary prior to plaintiff’s retirement.” Panetta, supra at 491-492.

The Appellate Court held that the valuation date for an individual’s SS benefit, like a federal pension, cannot be determined at the time of separation or at the time the Final Judgment of Divorce is signed. Both benefits are variable, and are contingent upon many factors such as age, salary, mortality, and years of service. Therefore the proper time to value a federal pension on the one hand, and SS benefits on the other hand, is at the time the parties begin to receive the benefits. Just as in calculating the coverture fraction for a defined benefit plan (“actual retirement benefit is multiplied by the coverture fraction and divided by two”).[10] The court held that since “the plaintiff contributed to SS during the marriage, the defendant who did not, was entitled to an offset against her share of his federal pension.” Panetta, supra, at 499. Therefore, “[i]n calculating the amount of the offset, the Marx formula is applied to the private employee’s actual SS benefit based upon her lifetime earnings. That amount is then deducted from her share of the federal employee’s pension.” Panetta, supra. The offset is not calculated until the recipient commences to receive the SS benefit. Panetta, supra.

Panetta had an additional complication, in that the plaintiff-husband received $530 per month in SS benefits. The Appellate Court held, “[t]he fairest and most equitable means is to deduct plaintiff’s actual SS benefit, $530 per month, from the defendant’s actual SS benefit when she begins to collect it, and then offset the remainder, subject to the Marx’s formula, against defendant’s share of plaintiff’s pension. In other words, the partial participant’s actual SS benefit is deducted from the full participant’s benefit and the remainder, subject to the Marx formula, is offset against the full participant’s share of the partial participant’s pension.” Panetta, supra at 500.[11] In the unpublished case Arce v. Agosto, T-1891-13T4 (App. Div. 2014) the Appellate Court denied the application of a former police officer to offset the former wife’s share of his pension against the marital share of her SS benefits. The parties’ agreement was silent on whether there should be an offset. In denying the former husband the relief, the Appellate Court relied on New Jersey courts having “long espoused a policy favoring the use of consensual agreements to resolve marital controversies.” Consequently, absent ‘unconscionability, fraud, or overreaching in negotiations of the settlement,’ a trial court has ‘no legal or equitable basis’ to alter matrimonial agreements.” [citations omitted]. Arce, supra at 11.

Conclusion

This article points out fundamentals in dealing with a gray divorce: (1) current spouses need to be married for 9 months to collect survivor benefits; (2) one year to collect spousal benefits; (3) ex-spouses need to be married for at least 10 years to collect spousal and survivor benefits; (4) an ex-spouse cannot be re-married when applying for spousal benefits on the record of a previous spouse; remarriage before the age of 60 disqualifies an ex-spouse from collecting survivor benefits on a former spouse’s record; and (5) always include the Panetta offset in your Marital Settlement Agreements when you have one spouse with a pension who did not pay into SS and a spouse that did pay into SS, to insure that the parties’ division of these benefits are equitable. Finally, there is no substitute for having an experienced SS expert advising you and your client in addressing the factors under N.J.S.A. 2A:34-23(b).

This article is an introduction and does not replace utilizing a SS expert. Within SS, there are exceptions upon exceptions not stated herein. The Policy Operation Manual for SS is online at https://secure.ssa.gov/apps10.

[1] Renee Stepler, Led by Baby Boomers, divorce rates climb for America’s 50+ Population. March 9, 2017.

[2] N.J.S.A. 2A:34-23(b)(1).

[3] 42 U.S.C. § 414(a)(2)

[4] 42 U.S.C. § 413(a)(2)(A)

[5] Social Security Benefits Planner, https://www.ssa.gov/planners/credits.html

[6] U.S.C. § 402(w)

[7] https://www.ssa.gov/cgi-bin/longevity.cgi

[8] 42 U.S.C. § 416(d)(1)

[9] Marx v. Marx, 265 N.J. Super. 418, 428 (Ch. Div. 1993) defined the formula to allocate a defined benefit plan:

- The total accrued benefit is to be determined when plaintiff is permitted to move her share of the benefit to pay status pursuant to the plan requirements.

- The plan administrator is to determine the coverture fraction and multiply the total accrued benefit by the coverture fraction.

- The product of the total accrued benefit times the coverture fraction is to be divided in half in accordance with plaintiff’s equitable share.

[10] Panetta v. Panetta, 370 N.J. Super. 486, 496 (App. Div. 2004)

[11] The Plaintiff-Husband was denied the offset because he failed to comply with the parties’ agreement, memorialized in their September 22, 1998 consent order. He failed to designate his former wife as the survivor beneficiary, and not his former wife as they had agreed, irrevocably precluding her from that benefit. Panetta, supra at 501.